A unique and vital mission

Who we are and what we do

Our mission and values

The NhRP is the only civil rights organization in the United States dedicated solely to securing rights for nonhuman animals.

Our groundbreaking work challenges an archaic, unjust legal status quo that views and treats all nonhuman animals as “things” with no rights. As with human rights, nonhuman rights are based on fundamental values and principles of justice such as liberty, autonomy, equality, and fairness.

The problem

The term animal rights has been around a long time. But what does it actually mean?

It surprises many people to learn that nonhuman animals don’t actually have any enforceable legal rights. For centuries, the law has viewed them as legal “things” with no rights. And, of course, their legal status doesn’t exist in a vacuum. Throughout history, humans have tended to treat the nonhuman world, animals and nature alike, as mere property that doesn’t matter in its own right but only in relation to human need or experience. This mentality, including denial of the fact that we too are animals and the idea that we are superior to other animals, is what makes it so easy to exploit nonhuman beings and their natural habitats.

Legally speaking, the rightlessness of nonhuman animals means that, for lawyers to help them in court, they have to make the case for how a human has been harmed by the nonhuman animal’s treatment or situation. If that sounds strange or unfair given all we know about nonhuman animals, that’s because it is, and many court cases that seek justice for nonhuman animals have been lost because of it.

That’s where we come in. Nonhuman animals need and are entitled to rights—actual legal rights, rather than symbolic declarations—and no being should be denied rights simply because of who they are. Simply put, the law has to catch up to what we know about nonhuman animals, and courts and legislatures have to begin figuring out which species are entitled to which rights on what basis. Until this happens, the law will remain chained to the past, nonhuman animals will continue to suffer under poorly enforced, insufficient, easily reversed animal welfare laws, and we humans are going to continue to destroy nonhuman lives and the planet we share with other beings.

Imagine a world where respect for freedom and dignity runs so deep we don’t extend it to nonhuman animals and where we make decisions at all levels based on justice, scientific evidence, and the interconnectedness of life on earth. That’s the world we’re working to help build.

Our history

Who we fight for

Great apes

Cetaceans

Our team

Steven

M. Wise

Gail

Price-Wise

Jane

Goodall

Elizabeth

Stein

Monica

Miller

Lauren

Choplin

Courtney

Fern

Peggy

Cusack

Shirley

Shtiegman

Spencer

Lo

Jake

Davis

Jeff

Fraser

Frequently asked questions

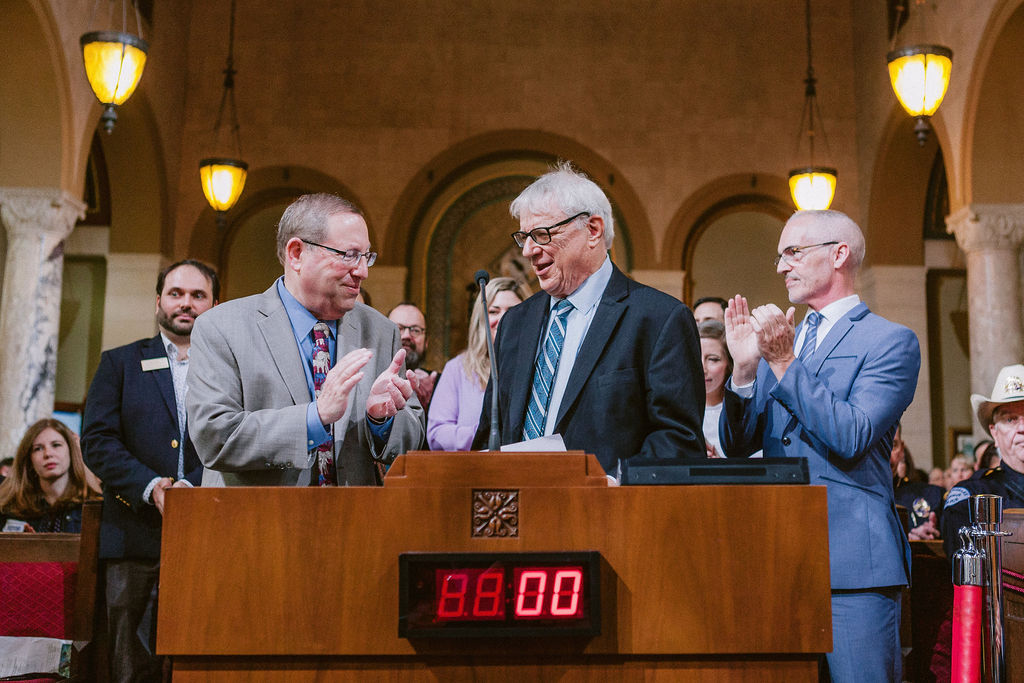

NhRP President Steven M. Wise founded the NhRP in 1995 as a project of the Center for the Expansion of Fundamental Rights. In 2012, it was officially renamed the Nonhuman Rights Project. We use the term “nonhuman rights” to remind people that human beings are also animals—the only animals with legally recognized and enforceable rights.

We are a civil rights organization because we seek recognition and protection of nonhuman rights within a civil rights framework. A civil right is a legally enforceable right that originates in notions of freedom and equality. The term civil rights might make you think of something only human beings can do, like voting, but broadly speaking, civil rights ensure basic freedoms and protect individuals against discrimination and oppression.

Civil rights can be bestowed by litigation or legislation. If a person or institution denies or interferes with a right because of an individual’s biologically immutable characteristics (i.e. membership in a particular group or class), this constitutes discrimination for which an individual can seek judicial remedy, including recognition and enforcement of that right. We argue the nonhuman animals we’re working to help are denied their liberty because of their species membership. Another word for this is speciesism.

They are members of species for whom there is robust, abundant scientific evidence of self-awareness and autonomy. Currently, this evidence exists for great apes, elephants, and cetaceans.

Self-awareness is the capacity to recognize yourself as an individual separate from the environment and other individuals. Autonomy is the capacity to make choices about how to spend your days and live your life. We believe it is morally and legally wrong to deprive self-aware, autonomous nonhuman animals of their liberty.

We care deeply about all animals. Some of us are vegan. Most of us live with companion animals. We’re as troubled as anyone by the suffering of individual nonhuman animals all over the planet and the many threats they face because of human actions.

However, as an organization, we’re committed to working within our existing legal systems and pursuing the strategies we deem most likely to succeed in courts and legislatures based on the values and principles courts and legislatures say they believe in, such as liberty, autonomy, equality, and fairness. Great apes, elephants, dolphins, and whales are not the only animals who are suffering, but they are the species we consider most likely to be the first to break through the legal wall that separates all nonhuman animals from all human beings. We’ll continue to follow the science and the law wherever they lead us and develop and refine our arguments accordingly.

The writ of habeas corpus, called the Great Writ, has existed for centuries and is meant to protect anyone who is unjustly imprisoned. When a judge issues an “Order to Show Cause” pursuant to a writ of habeas corpus—which has happened twice in our chimpanzee and elephant rights cases, resulting in the world’s first ever habeas corpus hearings on behalf of nonhuman animals—the detainer is required to appear in court to justify this imprisonment. We argue common law courts must recognize our nonhuman animal clients as legal persons with the fundamental right to bodily liberty protected by the writ of habeas corpus and then order their release to a sanctuary where this right will be respected.

“The common law is judge-made law that is based on the values held by judges. For a millennium, English-speaking judges have used the common law to decide cases that turn on general legal principles—such as liberty and equality—as opposed to those that require interpretation of statutes, constitutions, or treaties. Historically, the common law has been uniquely responsive to evolving standards of morality, scientific discovery, and human experience; judges have a duty to ensure that the common law keeps up with these evolving standards. In our extensive court filings, we argue they must do so—as a matter of justice and good public policy—where the liberty of nonhuman autonomous animals is concerned.”

It’s easy to get confused on this point because people often use the term animal rights to refer to what are actually animal welfare policies. In short, animal welfare focuses on improving the ways we treat animals without necessarily changing their underlying situations or prioritizing their interests above human interests. For example, you might pass an animal welfare law that increases the size of an elephant’s enclosure in a zoo: obviously this is better than not increasing it, but the zoo is still depriving the elephant of her liberty because people want to see elephants in zoos. We argue the elephant shouldn’t be in the zoo, period.

The fight for nonhuman rights focuses on the fact that nonhuman animals have their own inherent interests, just as humans do, and calls for these interests to be protected. All of human history, up to and including the present moment, shows that the only way to truly protect human beings’ fundamental interests is to recognize their rights. It’s no different for nonhuman animals.

At the same time, until we truly shift to a nonhuman rights paradigm, which may take many years, animal welfare laws are necessary to protect animals from human-caused harm. We’re grateful for the thousands of organizations doing this important work and are proud to count many of them among our friends and allies.”